Naomi Shihab Nye and Mark Twain on War and Revolution

Each carries a tender spot:

something our lives forgot to give us.

A man builds a house and says,

“I am native now.”

A woman speaks to a tree in place

of her son. And olives come.

A child’s poem says,

“I don’t like wars,

they end up with monuments.”

He’s painting a bird with wings

wide enough to cover two roofs at once.

-Naomi Shihab Nye

In early 2010, less than a year before the spark of the Arab Spring, I spent a season of my life traveling through Egypt and Jordan. I was studying public and cultural diplomacy, and took an intensive course in Arabic in Cairo, working for my room and board in a youth hostel in the old city, Funduq Africano (African House Hotel). We could walk to Tahrir Square from where I lived, and the society seemed - from my superficial foreign perspective - to be quite stable. I was the only international student who was living and working with Egyptians. I learned to play backgammon, and smoked hand-rolled cigarettes indoors. The only time we really talked “politics” was when we had to pay bribes to the police, or when my gracious Egyptian hosts let me know that I was making some sort of social faux pas that as a woman living like a local was totally taboo. My Arabic never got great, but it improved much faster than that of my fellow students, living in fancy foreign-style apartments on the luxury island of Zamalek.

After the month of language immersion, I traveled the rest of the country, then ventured into Jordan. I was first meant to be doing a longterm working stay at an eco-lodge in the Dana nature reserve, high on an ancient cliff overlooking the deserts stretching out toward the Israeli border. But after just a few days there, I began to see cracks in the moral facade of the proprietor. The Filipina maids (who were able to speak to me in basic Spanish) told me that they were being treated terribly, and when I tried (alone, in a remote desert) to talk to him about our concerns, he responded by menacingly trying to coerce me into some sort of seduction. I was mortified, and afraid, and paralyzed. So I ran away, in the middle of the night. I asked the maids to come with me, but how could I help them, really? They helped me find a driver to get me out of there and take me to Wadi Musa, where the tourists all gather before they visit the ruins of Petra.

Shaken, ashamed, and with a very out of whack budget due to the fact that I was supposed to be spending a month living for free in the desert, I convinced a little hostel to give me a huge discount in exchange for some social media and English translation help. That’s where an American journalist living in Amman found me, and rescued me.

He was on his way back to his apartment in beautiful Amman, and said I could stay with him there. His friend was working with UNRWA, and invited me to volunteer in a refugee camp teaching English to Palestinian women there. I will never forget the feeling of entering the camp, an established city in existence for over fifty years, but existing in a liminal purgatory. The cement block buildings, the schools, businesses, and family homes thrown up in a rush, but filled with precious family heirlooms dragged away from their previous homes, or more likely the homes of their parents. People born in this refugee camp were older than I was. Their hospitality and eagerness to learn about me, and to absorb the English language, was paradigm-shifting for me.

The camp was a bustling village, but Amman itself felt like Switzerland compared to everywhere else I’d visited during my Middle Eastern travels. It was there that I finally started to grasp what the international diplomacy community, the NGOs, the militaries, the governments, the corporate interests, the colonial forces were really doing. Wealthy international elites lived in luxurious Amman, working for humanistic causes and drinking European coffees, while carefully avoiding offending the real regional powers.

It was a relatively calm and complacent time in the area, with no formal blacklisting between Egypt, Jordan, or Israel, and I had the opportunity to visit friends in Jerusalem. As a student of spirituality and comparative religions, I was deeply drawn to the holy city and eager to see it. But to reach Jerusalem, I’d have to cross the Israeli-controlled border into the area that has always seemed to me to be the center of a Gordian knot.

The border crossing was an unnerving place, a seeming rift in the fabric of nationstates. I really don’t know how to describe it to you, as my memory comes now only in flashes. There were teenage girls with pony tails, chewing gum while apathetically grasping their automatic weapons. There were fearful and stressed citizens of various countries and occupied territories shuttled between stations. Everything was low-fi, disconnected, and confusing. This was not a place of genteel diplomacy and international ideals, it was a place of suspicion, disdain, and apartheid.

I was sent from booth to booth, interrogated by multiple guards, and noticed that with each round of questioning and checking of my papers, the tone became more sneering, more invasive, more accusatory. Finally, I was told by a person who looked like a military barbie that I was to be denied entry by the Israeli government. They had decided that I was a risk apparently because there were rumors of a peace demonstration being planned that weekend, and I looked a bit too much like I might be “the type” to participate in these activities. They stamped a huge red X on my passport, and sent me out, back to the Jordanian side of the border. Dejected, a bit shaken, but weirdly relieved that nothing worse had happened to me, I got onto a dusty bus back to my friends in the city where a thin veneer of order and civility was lacquered onto the fraying fabric of society.

I went on to spend more time in Amman, before eventually returning to Cairo and flying home to California. Soon after of course, I watched in shock from thousands of miles away as my friends in Cairo took to the streets to demand democracy and overthrow Hosni Mubarak. I would never have imagined the Arab Spring bubbling up in Cairo, because although I had dug deeper than many of my fellow travelers and expats, I had still lived in a bubble, wrapped up in soft gauze to protect and blind me from the anguish of the people.

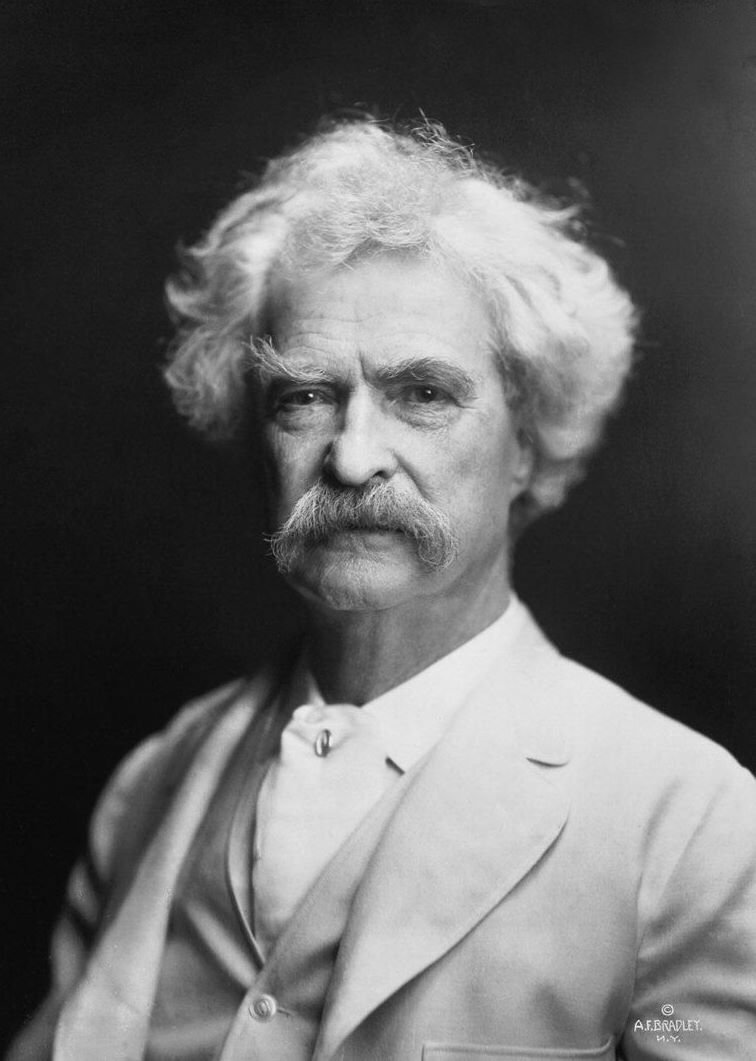

Sometimes after too many hours of skimming various news media and opposing opinions, looking at these crises, these attacks from too many conflicting perspectives, I need to take a step back and view things from about one hundred years away. In 2011 I shared these words from Mark Twain, and will do so again now. For context, he was quoted in defense of Russian revolutionary writer Maxim Gorky in 1906 in the New York Tribune:

“I am said to be a revolutionist in my sympathies, by birth, by breeding and by principle. I am always on the side of the revolutionists, because there never was a revolution unless there were some oppressive and intolerable conditions against which to revolute.”

The intolerable and oppressive force in this case being the Israeli government and military, funded by the United States. I like to think Mark Twain would agree with me in my fervent desire for a free, independent, internationally recognized Palestine among many many other necessary changes to give reparations and self-determination back to the peoples of the Middle East and MENA regions (and the whole globe) after the ravages of colonialism, empire, and the Cold War.

I don’t know what what we can do as isolated individuals in our own homes. I don’t have a solution, but I do know I have to at least take the time to think deeply and meditate on Palestine. I’m writing down what I personally, truly feel about what’s happening right now. I’m asking myself how it is connected to me, how is it connected to Brazil, Colombia, the US, India, and other regional conflicts, catastrophes, and crises playing out simultaneously and throughout history.

I’m asking myself what healing I can create in this world.